This article was originally written as class notes for a class given at Atlantian University. It is in two parts – the first details a timeline of fashion evolution, while the second provides construction details. Most of the photos included can be enlarged by clicking on them.

For the purposes of this class/site, “Gothic Europe” refers to France, England, and areas which followed the fashions of the courts of these countries. Depending on when in the time period one refers to, this could include Wales, Burgundy, Guelders/Cleves, Bohemia, parts of Germany (though Germany is not a focus of the class) and more. However, it does not cover areas like Italy and Spain, both of which had separate fashion trends which, while they overlap in some ways with “mainland” Europe, have enough variation to consider separately.

There are some details which seem to follow geography – while overall trends can be generalized, to accurately say a given outfit is appropriate for a time and place requires sources from that time and place. Hair and hat/veil styles, sleeve treatments, and other details may be seen only in the art from a given area, and should be assumed to be a regional variation. For instance, Margaret Scott refers to “Teutonic” variations in clothing, as fashion moved more slowly and with different details as one moved farther north and east from France.

Historic Background

At the beginning of the time in question, the Hundred Years’ War has gone into a truce. Charles VI is now King of France, though prone to occasional madness. The courts of Burgundy and Berry are centers of culture. The Black Death is mostly in remission, though it will return in 1400 and 1438-9.

Centers of art and fashion at the time included Paris and the courts of Burgundy and Berry; England was considered something of a backwater and Isabella of Bavaria “was made to change into French dress because her German clothes were too plain by French standards, before she was presented” as a prospective bride to Charles VI.

Part One: The Evolution of Women’s Clothing

Before 1390:

Women in the 1380s were wearing 2 layers – “cote” and “surcote” in French, or (perhaps) “kirtle” and “gown” in English. The English often used French or Latin – tunica and supertunica – words in inventories, and the names of garments often did not change with their appearance, nor did they always specify which layer was indicated by a term. Other words used include cote-hardie, jupone, and paltok, and of course houppelande as that style developed later.

Weeper (Joan, daughter of Edward III)

Tomb of Edward III, Westminster Abbey

1386

The sleeves of these gowns – specifically the top layer – were often finished with “tippets” (the trailing white bands shown around the upper arm.) Not separate pieces, these were instead part of the sleeve of the gown and showed the fur linings.

Hoods were often worn, especially outdoors, and were we to turn back these ladies’ hoods, we would probably see hair braided to the sides of the temples.

These outfits were very similar, plus or minus some details, to those worn in the previous 40 years – at least one fashion historian has called the period between 1350 and 1390 a “fashion freeze” in France, due to the Hundred Years War and the Plague . Fashion, however, is about to begin changing rapidly – after this point one will be able to look at a garment and identify its decade.

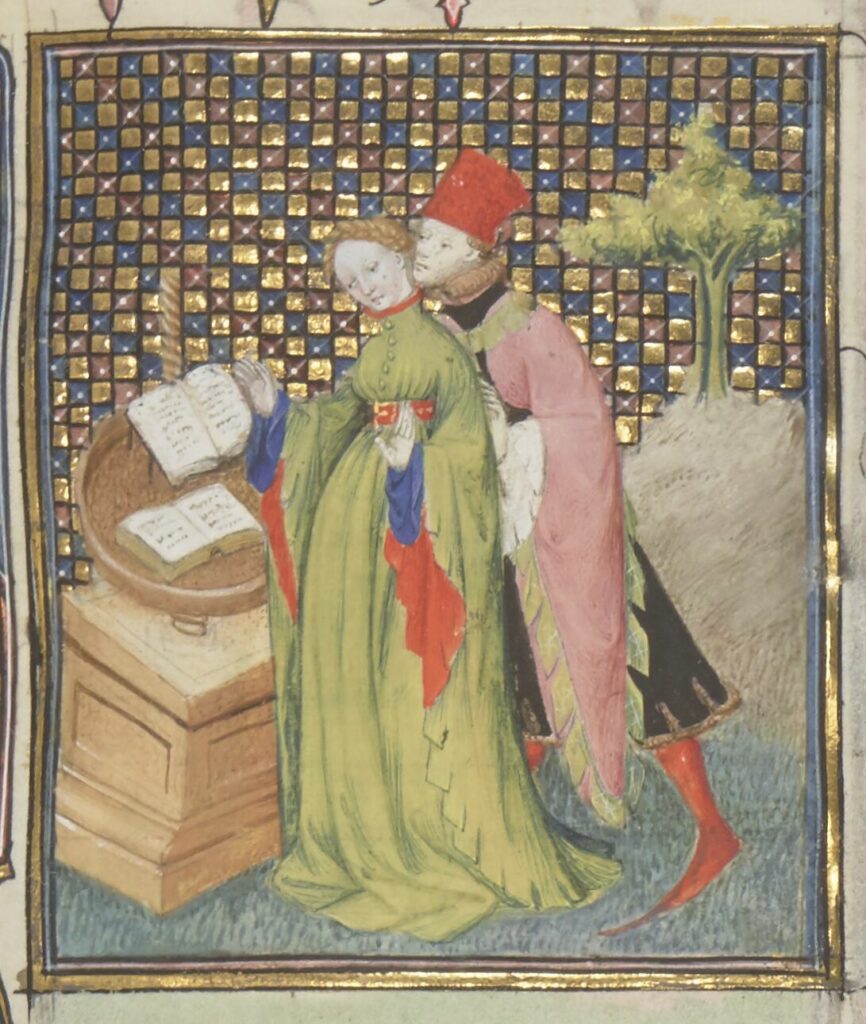

1390-1400

In the last decade of the fourteenth century, fashion moved in two distinct directions. The first was towards the scoop-necked gown. Rather than the more “boat-shaped” neckline of previous decades, gown necklines became distinctly scooped, in some images even showing cleavage.

Tristan de Léonois

Français 335, Folio 346

Sleeve styles also became more varied, with long, narrow tippets falling somewhat out of favor for straight sleeves or even a slightly more open or flared sleeve. Tippeted gowns were still worn with sideless surcoats, however. Undergowns often had cuffs extending as far as the knuckles of the hand, with or without buttons.

Alice Giffard, wife of Sir John Cassy

1390-1400

(England, Deerhurst, Gloucestershire, St. Mary’s Church)

Alternately, the houppelande or gown also appeared. In its earliest incarnation, this was a very high-necked garment, buttoned to the chin, worn unbelted. Sleeves might be straight and loose, or bagged, but generally allow the undersleeves to show at the cuffs. These gowns were similar to mens’ gowns of the time, which may be their origin.

Hair was dressed in “poufs” or modest temple-buns – the “puppy dog ears” braid, as it is known in some circles, had virtually disappeared by this time. “Stacked” veils were still worn with gowns, though the padded roll would not make its appearance until 1400.

1400-1410

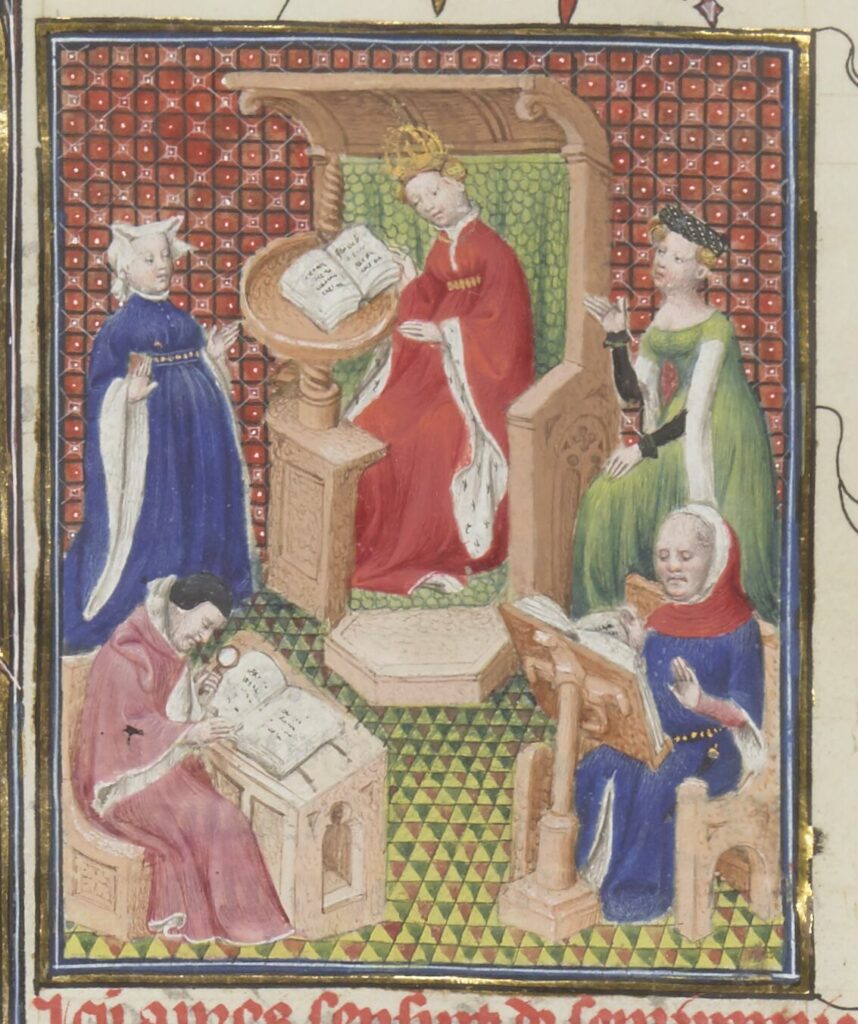

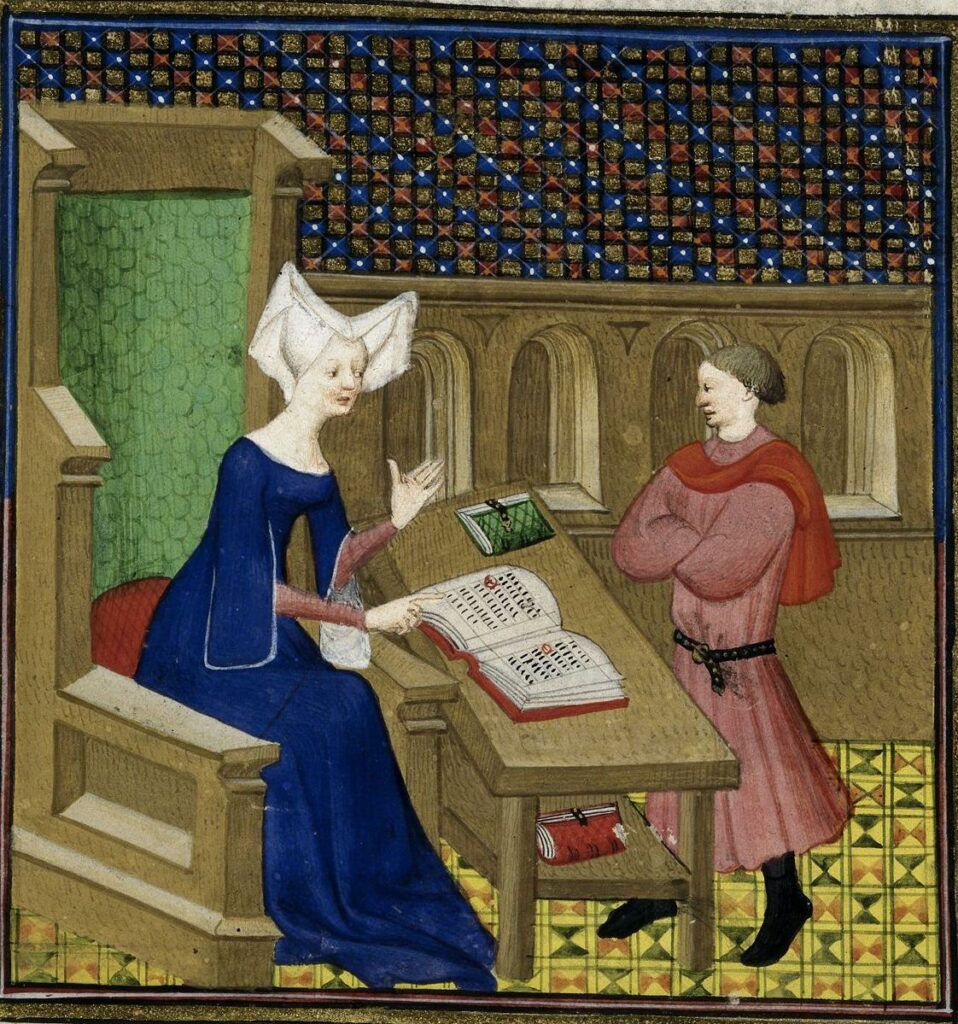

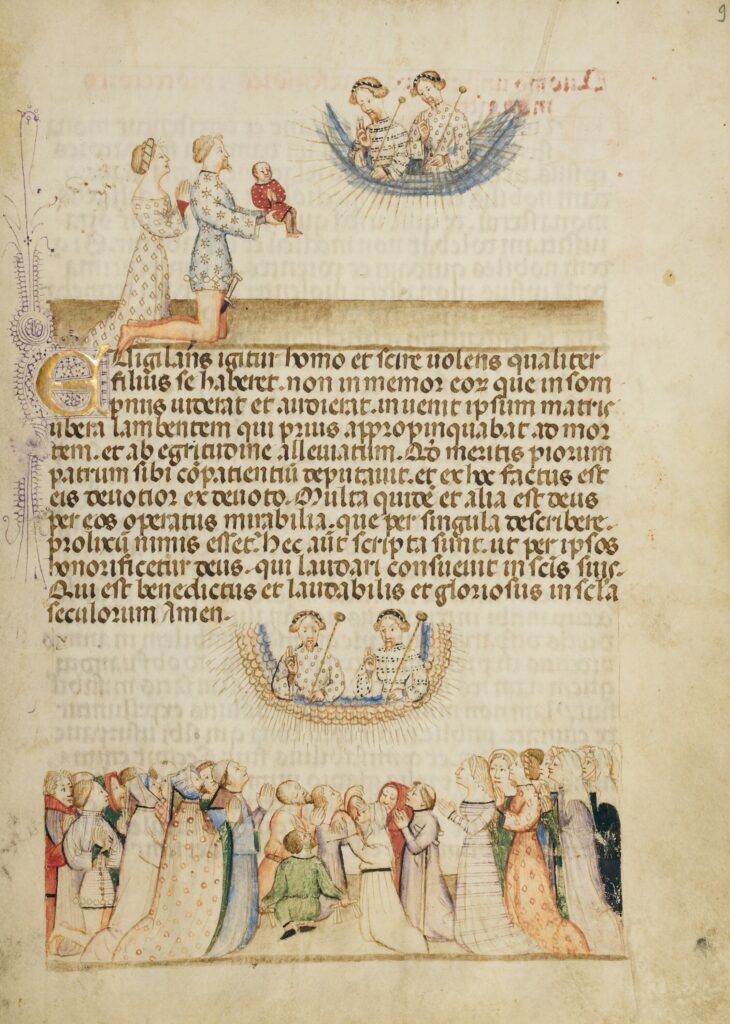

Giovanni Boccaccio, De Claris mulieribus,

Français 598, folio 127r

1403

After the turn of the century, the simple gowns seen in the previous decade became increasingly elaborate, with both “scoop-necked gowns” and houppelandes being worn with various elaborate sleeve options, such as bombard sleeves that drape to the ground, sometimes with dags.

One of the most obvious changes is that the houppelandes are now belted, at roughly the level of the natural waist or somewhat higher. (The appearance of belting directly under the bust is partially due to the artistic style at the time.) Collars are still high, though starting to flare around the face and fall away from the neck slightly.

The “cuffed” appearance of the undergown sleeve is exaggerated, with draped fabric shown over the hands of many figures. (These cuffs were known as “moutons”.)

The scoop-necked gown is still worn, though often not by the “principle” figure in a given illumination – queens and older women are more often shown in the formal houppelande, while younger or less important women wear the tighter gown.

Two other sleeve treatments are found in association with the scoop-necked gown – a late form of tippets and the “flat” sleeve.

Both of these are logical, gradual progressions from earlier sleeve forms. The extremely long pendant sleeve was also made famous in a more modest format by Christine de Pisan.

(Robert and) Clarices de Freville

1410

Various headwear is worn, including bourrelets (padded rolls) over temple buns, with or without veils, and various arrangements of veils arranged into “horns” – these were known as “houves”. Younger and/or unmarried women, of course, showed greater amounts of hair.

1410-1420

Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, April miniature

1415

Fashion in the next decade remained substantially similar to that in the previous decade – both scoop-necked gowns and houppelandes were worn. However, many of the trends that had already started continued in the same directions.

Houppelande collars continued to widen and fall away from the face, spreading over the shoulders.

Hairstyles also continued to become wider and taller, as do the bourrelets worn with them.

Scoop-necked gowns are rarer, and are seen with either wide flared sleeves or sleeves which are nothing but flat fabric gathered to the sleeve head. This “pleated on” sleeve is also seen in at least one example on a women’s houppelande, but more often on men.

A “lining” collar was often worn over the fur collar of the houppelande, perhaps to protect it from bare skin – it is unclear whether these were attached to the houppelande or a separate piece.

The progression of hats towards taller and wider continues.

1420-1430

1415-1423

By 1420, the scoop-necked gown had almost disappeared as an outer / “fashion” layer, though was occasionally seen. The houppelande, on the other hand continued down the path towards what is now known as “Burgundian” fashion. At the beginning of the 1420s, the collar of the houppelande had spread to the point where Margaret Scott refers to it as “a small cape” around the shoulders. .

The pleating in the body of the gown has become both shallower and more regularized, after reaching its deepest point in the previous decade. Both extreme bombard sleeves and narrower sleeves are observed, along with wide bourrelets and even wider and taller houves. However, on a note of practicality, mouton sleeve cuffs have disappeared. Belts have widened, though not to the several-inch width they will reach after 1450.

1430-1440

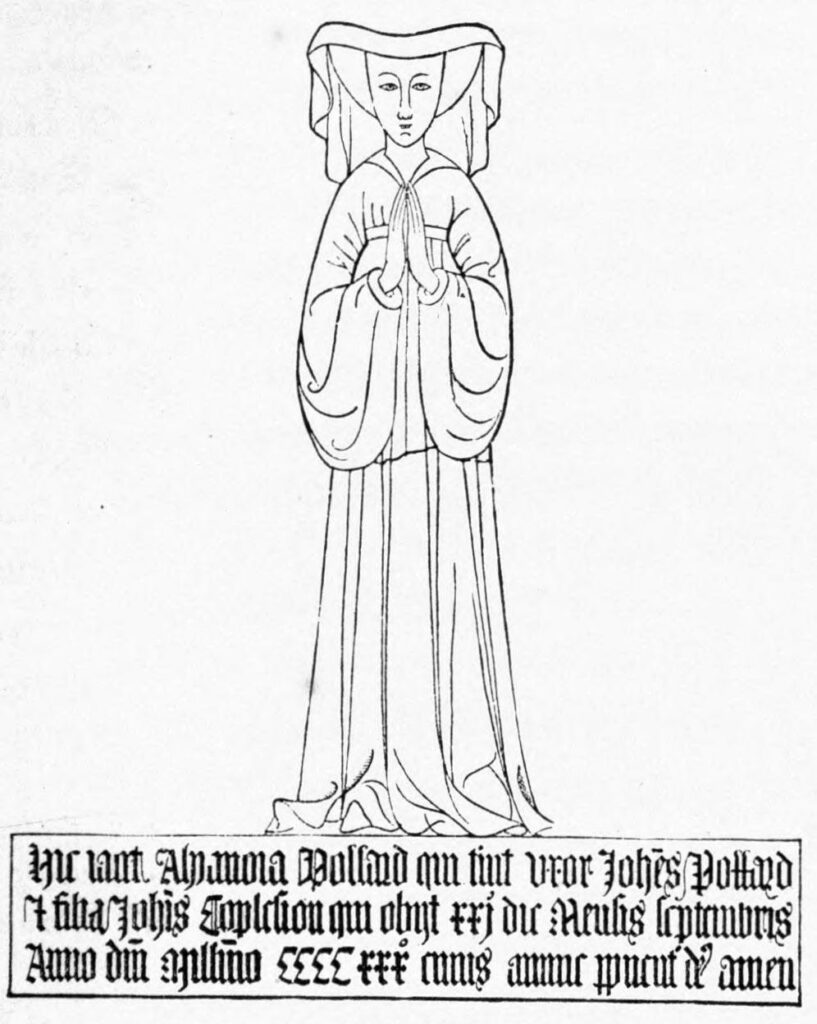

Alyanora Pollard,

St Gile’s Church, Torrington, Devon, England

1430

Art from the 1430s changes significantly – there are not as many illuminated manuscripts, but Flemish portrait artists like van der Weyden and Van Eyck are active.

St. Mary Magdalene reading, Rogier van der Weyden

~1435

(Ignore the veil in this – it’s religious allegory. However, Mary is wearing a fairly typical gown.)

In clothing, the body of the houppelande has significantly narrowed – pleats extend only a short distance above the bustline, and the robe itself has opened around the neck, with visible fur often extending below the belt.

”Lust” as a well-dressed woman, 1436-1440, British Library, Yates Thompson MS 3 f. 172v

Collars are much narrower, and in many cases so are sleeves.

Margretha Van Eyck

1439

Hair is still dressed in horns, but although most of these images seem to indicate a decrease in size, that is more a function of the social class of the wearer than of actual decrease, as shown next decade.

1440-1450

Courtiers in a Rose Garden Tapestry

1440-1450

In the 1440s, the robe is open all the way to the belt, showing the gown underneath. (Later images show a decorative placket pinned to the kirtle to cover the undergown’s lacing; it is unclear whether that occurs this early.) The lacing of the robe, often shows across the opening. Some gowns are even starting to move towards the edges of the shoulders

Hats have become quite tall, and are often ornamented with liripipes and dags to resemble the chaperones worn by men in this period. Alternately, thin veils are worn over the horns.

Belts are significantly wider – in some art, they appear to be up to 3 or 4 inches.

Sleeves are universally narrow to the arm, and many gowns have a wide band of fur turned up at the bottom.

Germany and Points East

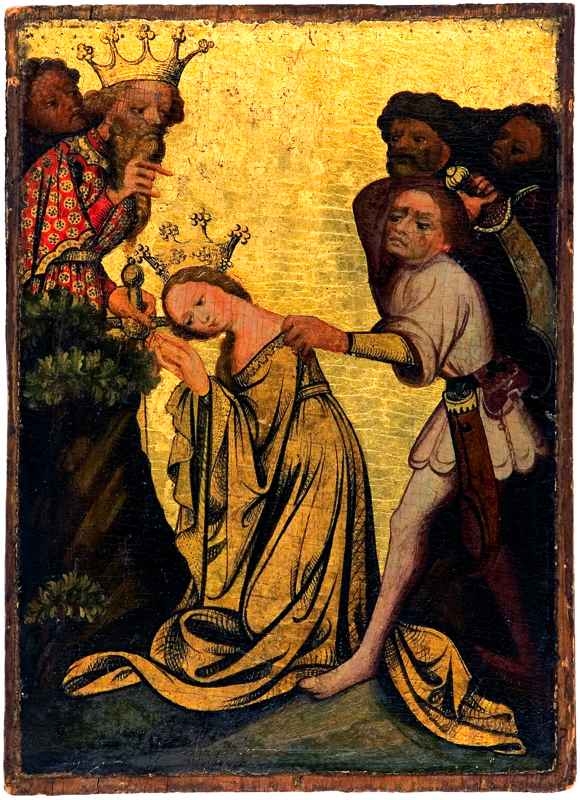

Panel, “Passion of the St. Barbara”

1390 – Bohemia

While Guelders, Cleves, Bohemia, and other areas followed fashions from the Paris courts, there were subtle regional differences.

The royal court of Bohemia was very closely linked to the royal court of France at this time – Charles IV and Wenceslas IV of Bohemia were uncle and cousin, respectively, to Charles V of France. The biggest difference in fashions shown in art is the placement of trim – the trim around the neckline of the gown shown in the saint’s image is not often seen in French art.

Hours of Catherine of Cleves, MS M.917 folio 1v, 1440

On the other hand, later in the period in question, German, Bohemian, and Flemish fashion somewhat lagged behind that of France proper, and continued to have stylistic quirks. For instance,

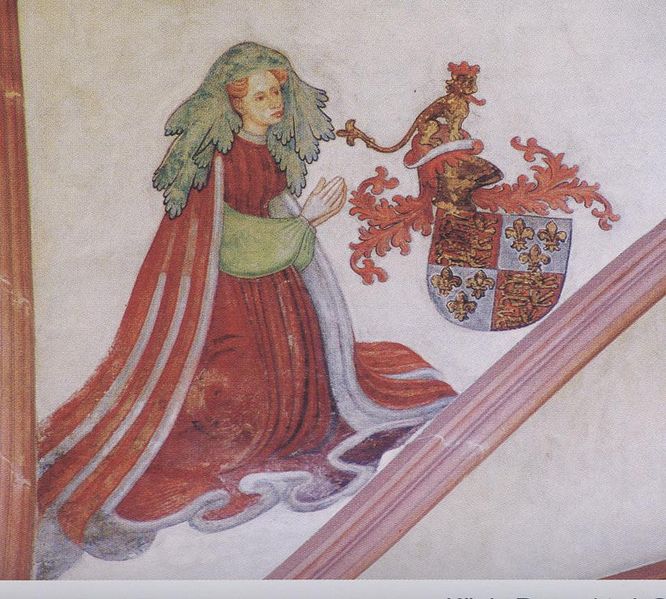

Blanche of England (wife of Elector Ludwig IV, 1409), Wall painting in Stiftskirche in Neustadt an der Weinstraße

Catherine of Cleves was painted in her book of hours in a gown which would have been stylish in France more than 20 years previous.

Hats, too, varied – although one occasionally sees women wearing dagged chaperones in French art, they appear to be far more common in German/Bohemian/Flemish images.

Italy

Italy, too, followed the International Gothic style, but with its own regional variations. As the 1400’s progress, fashion on the Italian diverges both from “mainland” Europe and from itself – the city states of Italy will have individual styles by the 1460’s.

Paolo Uccello, Birth of the Virgin

1435 (Florence)

In the early 1400’s, however, the most distinctive element of Italian gothic dress is the rounder silhouette, and the softer drape of the fabric.

Because patterned silks were imported through Italy, they are far more commonly represented in Italian art than French (Scott and Museum). Fur linings found in colder climates seem, for obvious reasons, to be absent or rare.Hair taping, too, is a uniquely Italian fashion. Later, while the gown evolved into the houppelande elsewhere, the Italian version became the cioppa or opppelandra, with distinctive features such as the rounded neckline.

Part Two: Achieving the Gothic Look

The Gothic Silhouette

One of the most distinctive aspects of women’s fashion from 1390-1440 is the silhouette considered the ideal of female beauty throughout this period. Needless to say, all women did not meet this standard, but there is textual evidence that it was a goal.

The ideal gothic woman was tall and slender, with reasonably small breasts, placed high on the chest. Even unmarried and “virginal” beauties were painted in such a way as to suggest fertility and pregnancy, as shown in both of the images on this page. Despite the long sweeping lines from the high-waisted gowns to the past-floor length hems, somewhat short legs in proportion to the rest of the body were nearly universal in nudes of the period.

”The Fall of Adam”

Hugo van der Goes

1470

Other points of beauty included a rather high forehead, which was achieved by plucking the eyebrows and forehead hair, and blond hair.

Of course, while many women of the day sought to achieve a fashionable silhouette and visage, their more conservative contemporaries criticized their attempts. Eustache Deschamps write satirical verse about the “sacks” sewn on women’s chests to mimic “round, petite, firm” breasts . Worse, sermons were written about the plucking of foreheads and the punishments those who indulged would receive in the afterlife – devils would thrust burning needles into the places where hair had been removed .

Getting Dressed – Garb Layers Worn

The three basic garb layers observed in art at this time are the shift/chemise, the cote/kirtle and the surcote/gown/houppelande. However, recent archaelogical finds (the bras at Lengburg Castle) somewhat throw that into question, as they don’t fit neatly into those categories, as do mentions of extra “underwear” layers for warmth in period texts. Regardless, the three basic layers are a great place to start.

Shaping the Body

In order to approximate the Gothic ideal, one must wear the appropriate layers to shape the body – support of the bosom and “smoothing” of the torso contribute to achieving the look. Without appropriate undergarments, the houppelande tends to look saggy and can cause the wearer to appear heavier than they actually are.

Two approaches can be taken – either support can be built into the “shift” layer or the “cote” layer.

Consult www.cottesimple.com or www.bymymeasure.com for fitting instructions for the cote layer – these fitting techniques can also be used to fit a laced chemise for support, or even a garment similar to the new “bras” discovered at Lengburg castle.

The Shift

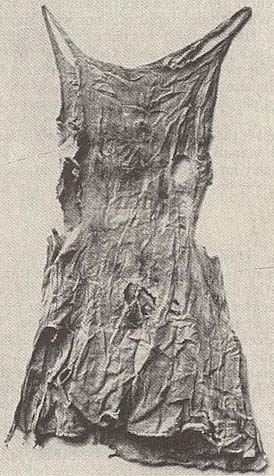

Two types of shift are seen in period art, a calf-length loose tunic and a sleeveless shift.

Paris, BnF, Arsenal, manuscrit 5070 fol. 387

1432

Examples exist, or in one case did exist, of the sleeveless chemise – Kohler’s History of Costume, an otherwise unreliable source, does contain one compelling photo of a shift which was apparently lost in WWII.

Some of the sleeveless chemises appear to have a different construction method than others – while some seem to be a straight “slip” like the missing extant example, other appear to have sewn on straps and even rib bands . Of course, it is also unclear how or if these garments might be related to the recent bra finds.

There is no conclusive evidence of women wearing underwear at this time.

On a practical note, a sleeved chemise does perform the important task of being a washable layer between the skin and the next layer. White linen is the appropriate material to make these garments from; references to silk smocks were probably making allegorical or fantastical rather than reality.

The Cote

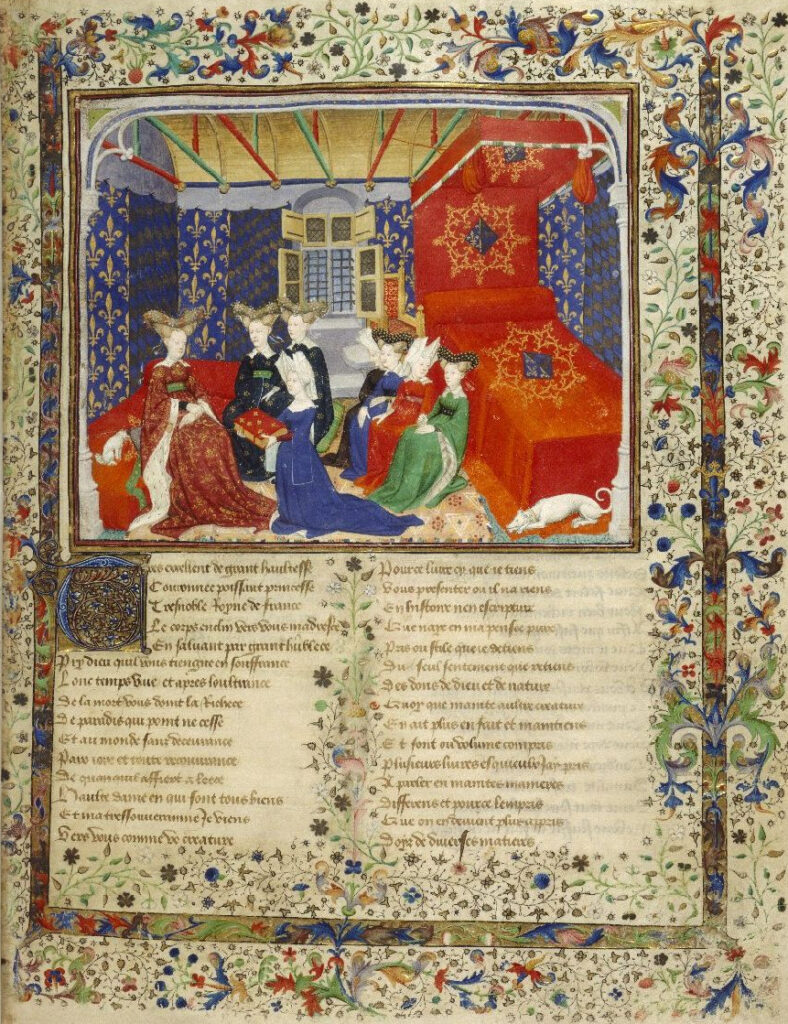

While in many of these images the cote is barely visible, it is essential to the “look” of these outfits. In the picture above, it is visible only in the sleeves of the queen and underskirt of the lady in waiting. However, not only is a fitted cote often essential to the silhouette (in the absence of a supportive underwear layer) but it is also the “everyday” gown of the period, as shown:

Early cotes appear to be simple 4 panel gowns, laced at the front, with no waist seam. There is some evidence of an 8 panel style, as seen on the famous portrait of Agnes Sorel as the Virgin Mary. Substantially, however, cotes/kirtles remained similar in styling to the earlier 14th century versions with the exception of sleeve details such as cuffs or full sleeves.

A waist seam appeared in kirtles as early as the 1440s, which complemented the more defined waistline of that period. Short sleeves are also a possibility for the cote in this time frame, though far less common than one would think given their prevalence in the SCA .

These gowns were most likely wool lined in linen.

The Gown

Falconry, The Devonshire Hunting Tapestries, late 1420s

This layer is the “conspicuous consumption” layer of the outfit – gowns made of wool, silk, velvet or brocade are all appropriate depending on the time, place, and social class of your chosen outfit. Linings were most likely fur, though fabric linings are also common, especially in Italy. There are even instances of what appear to be brocade linings, though these may be artistic license to create a more attractive tapestry.

In general, the aesthetic was based on expensive fabric rather than extensive decoration; though this may be a function of the size of the art rather than reality. Inventories do reference embroidered gowns, though these often belonged to men.

Regardless of the type of fabric, it is crucial to use enough fabric to match the period look.

Extant Gowns

Houpelande of Jan Zhorelecky,

1396, Prague Castle

No extant women’s houppelandes have been discovered as of yet. However, there are garments that may give us clues to their construction. The houppelande of Jan Zhorelecky, dated to 1396, was constructed as a series of gored panels, and although a male garment, does fall in similar folds around the skirt. John the Fearless owned a houppelande made in 24 “girons” , and gowns such as the Herjolfnes 38 and 39 were also gored .

Patterning the Scoop-Necked Gown – 1390-1410

Like the cote, the scoop necked gown seems to be based on a 4-panel construction, with gores placed in the skirt and various sleeve treatments.

Unfortunately, the best way I have found to produce this type of gown is via draping – the “pin fabric to the body and cut away everything that does not look like a gown” technique, so I cannot provide a step-by-step pattern.

If you have a well-fitting cote pattern, one can simply add an extra 1” of ease (total) to the body of the garment and make a well-fitting gown to go over that cote. Depending on your body proportions (specifically shoulders vs ribcage vs bust), you may even be able to make this gown without fastenings and slide into it – it’s worth trying before you go to the effort of sewing eyelets. Hidden lacing is also period (again, see Agnes Sorel) and gowns without visible lacing may be laced on the side, though probably not in the back or side back at this point in history.

If you do not have a cote pattern, start by making a cote, and either use the same pattern or drape your gown over the cote – a gown based off measurements while not wearing the cote or other body shaping garment will not fit properly.

Other tips I have learned:

- As you drape or fit the garment, pull the shoulders up and to the outside to remove excess ease. This will cause the neckline to cling more tightly and not gape.

- A high neckline in the back helps support heavy sleeves and low-cut shoulders and necklines.

- Gore placement is crucial for silhouette – for instance, a “slinky” gown such as those in Francais 75 (above) requires gores that start just as the hips widen, emphasizing the waist/hip ratio, while some of the more Italian styles (for instance, those shown in the various Tacuinum Sanitatis manuscripts) require a gore that starts higher, directly below the bustline. This can also be used to tailor a garment to flatter the wearer, depending on the wearer’s proportions – gores should always start above the widest part of the hips to avoid pulling, for instance.

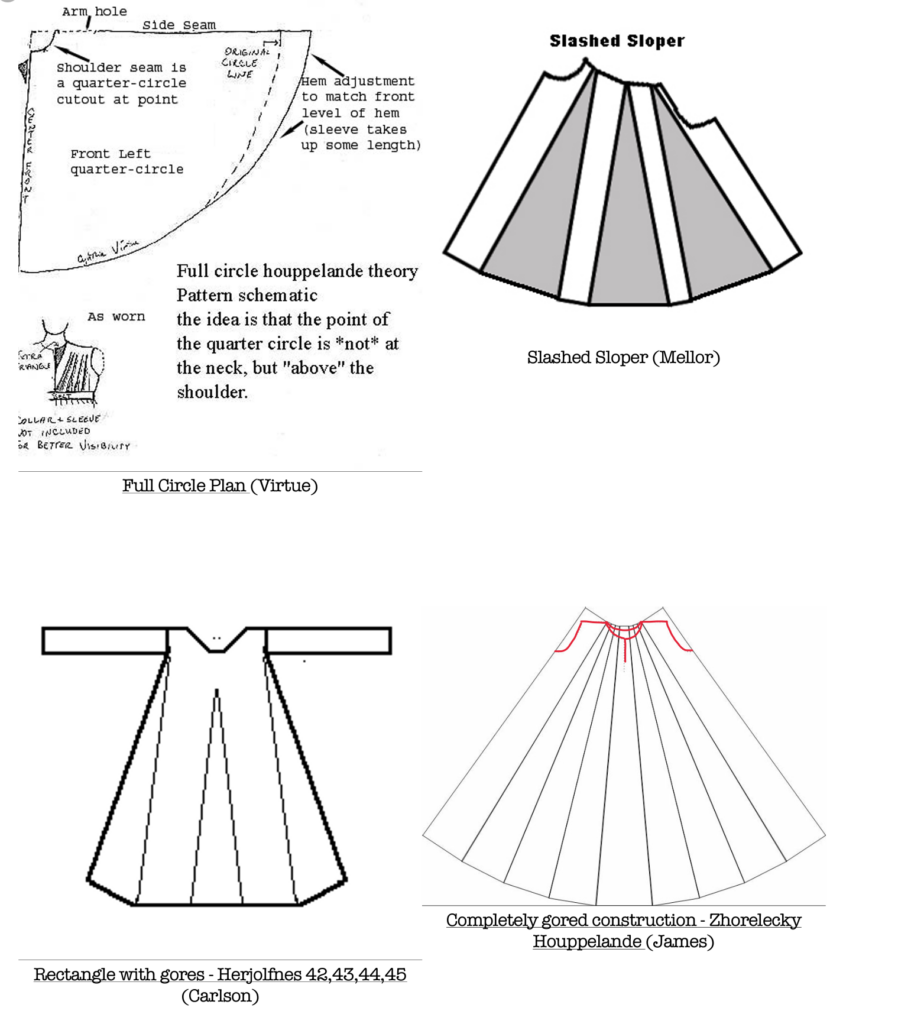

Patterning the Houppelande – 1390-1440

Pros and Cons of Construction Approaches

| Full Circle | Slashed Sloper | Rectangle with Gores | Fully Gored Construction | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Originator | Cynthia Virtue (SCA) | Helen of Greyfells (SCA) / Rashid al-Gyanji (SCA) | Herjolfnes Gowns | Zhorelecky houppelande |

| Period Technique? | Conjectural | Modern Pattern Drafting with period references | Period artifact | Period artifact |

| Pros | Good pleating and drape | Good pleating and drape | Very fabric conservative | Falls into perfect folds along gores, reasonably fabric conservative for effect. |

| Cons | Uses too much fabric, can be bulkier than manuscripts would indicate. | Modern technique | Doesn’t provide correct drape or enough pleating at chest. | Shoulders must be cut properly in order for pleats to reach shoulders instead of neck. |

Sample Layout and Instructions

Although I use draping techniques to determine the final shape of each piece, using mathematics to determine the approximate sizes of these pieces is extremely useful in determining a fabric layout which takes advantage of your fabric.

For a houppelande, the key measurements to consider are the bust, how much ease around the bust you need for pleat depth, and how generous the hem needs to be (too much is almost enough).

As an example, one of my gowns (details to be added in a future post) was made with only 6.75 yards of 45” silk, but has a 64” measurement at the bust and a 226” hem. To approximate a layout, the procedure was approximately as follows:

- Determine bust measurement, both around the body and distance from shoulder to bust.

- Decide how deep the pleats need to be, based on the style of gown you are recreating, and how much larger than bust measurement you’ll need to make your gown to create those pleats.

- Determine shoulder to floor distance, and how much “hem puddle” and train you want. (Remember – conspicuous consumption!)

- Decide how much fabric you wish to reserve for sleeves. This is most easily accomplished by draping them in muslin before starting on the final pattern. This, in fact, was a period practice – the inventories of Isabella of Bavaria note that in 1403, her household purchased five and a half ells of cheap cloth “to pattern the sleeves of a houppelande”. .

- Lay out rectangular and triangular pieces on your fabric – or on a scale model of your fabric, paper or computer – the length of these pieces will be the shoulder-to-hem length, plus a few inches for adjusting the shoulders and for hems. Measure each piece at the bust height you’ve established, and add them all up to ensure you’ve built in enough room for pleating.

- Like the earlier scoop necked gowns, these gowns drape better if the fabric is pulled outwards towards the shoulders – several authors, in fact, recommend a curved shoulder seam to emphasize this effect – which cause the pleats to radiate towards the shoulders instead of the neck. This better approximates period art, but does require the insertion of small, v-shaped pieces in the front and back of the gown’s neckline to fill in the gap created. (It also makes the evolution of the later Burgundian v-necked gown very logical.)

Hats and Accessories

The items worn with the houppelande are a class – or several – to themselves, but here are some points to consider as you complete your outfit.

- You are not dressed without a hat or haircovering, with the exception of certain ladies of the 1390s-1400s – and they wore their hair in fairly elaborate styles. (Furthermore, without the headwear for balance, a houppelande can look like the pile of fabric that ate its wearer. Don’t be that person.)

- A belt, too, with only a few exceptions, is crucial. Leather or tabletweaving is appropriate, and there are examples in art and extant pieces which are elaborately decorated, whether with embroidery or the jeweler’s art. Later, wide belts must be fairly stiff in order to not fall into creases as they are worn.

- Hosen and shoes are important, too – knee length hosen were most likely worn, and the pointed toes on the shoes are useful for walking with a hem that is longer than your height.

- “Fun” accessories include necklaces (of very specific styling), rings, baldrics and folly bells. Paternosters of many different sorts were also a key piece of jewelry.

Bibliography

Please Note: Only sources used for written information cited in text are listed below; images are individually linked to sources in captions.