What, Where and When:

Miscelin Bread is a a mixed bread of barley, rye and wheat. Bread such as this was eaten throughout period. Most of my research, however, has focused on 14th/15th century France. This is a bread that might have been eaten by servants or the middle class in 15th century Europe. This bread and documentation was entered in the 2006 Royal Baker of Atlantia competition.

Original Recipe

There are very few existent bread recipes from pre-1600. Among those are the bread recipe in Platina, the recipe for “Rastons” in one of the Harleian manuscripts, and the recipes for “Fine Manchet” and “Restons” in The Good Huswife’s Handmaide for the Kitchen .

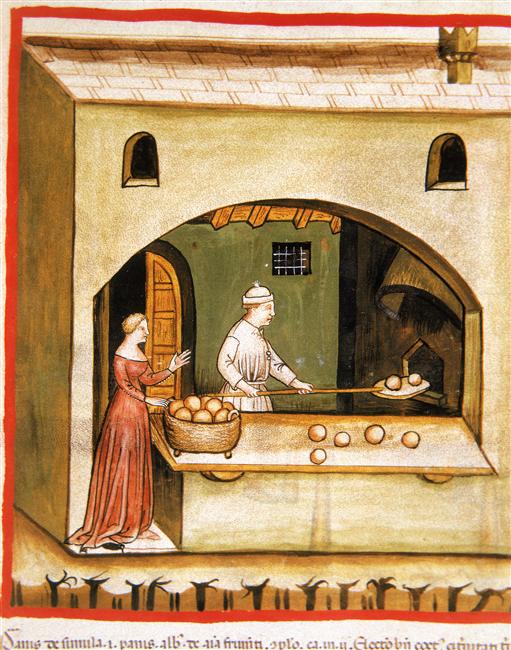

Tacuinum sanitatis (ÖNB Codex Vindobonensis, series nova 2644), c. 1370-1400 Looking at the recipe from Platina, who wrote in Italy in the late 15th century, it says:

“Therefore I recommend to anyone who is a baker that he use flour from wheat meal, well ground and then passed through a fine seive to sift it; then put it in a bread pan with warm water, to which has been added salt, after the manner of the people of Ferrari in Italy. After adding the right amount of leaven, keep it in a damp place if you can and let it rise…. The bread should be well baked in an oven, and not on the same day; bread from fresh flour is most nourishing of all, and should be baked slowly”

I did not follow this recipe exactly, but my methods were similar.

Discussion

Instead of making a bread fit for the “lord’s table”, I instead chose to make a bread more suited for the members of the lords’ household. Terrence Scully, in “Early French Cookery”, says that “the most commonly available bread at this time was undoubtedly the large loaf that was made from a mixture of wheat and rye flours. This was miscelin or meslin bread, the bread eaten by ordinary bourgeois, and bought by the wealthy to feed to their servants. The name of this bread, deriving as it does ultimately from the Latin verb miscere, to mix, points to its alloyed composition, an economical compromise between quality and cost.” This is the bread I have chosen to redact.

Most medieval households likely bought bread instead of baking it themselves. This is shown in Martha Carlin’s article, “Fast Food and Urban Living Standards in Medieval England”, in which she states that at least 2 of the 14th century household record books she studied show neither bread kneading troughs or oven peels, or even flour or wheat, are recorded in the inventories. Because of this, there are few specific recipes for bread, and I chose not to work directly with any of them.

The first question when making bread is “how to make the bread rise”. Since my house has a tendency to kill starters, and since none of the brewers I know had made beer recently enough to give me yeast, I chose to work with commercial, packaged yeast. I did, however, mix it with beer and proof it to simulate beer barm.

The next question is that of type of flour to use. Scully also states that “Several cereal grains were commonly used in the making of breads. The quality of bread varied according to the grain that went into the flour, or the mixture of grains, the care taken in its grinding, and whether or not the bran of the grain was removed from the flour. As a plant, wheat requires a good soil to flourish, but spelt, barley, oats and rye can grow well even in relatively poor soils. Though barley and oats were employed in bread either by themselves or mixed in combination with themselves and with such other flours as from ground peas or lentils or vetch, rye was really the only cereal grain that proved itself at all popular as an alternative to wheat for this purpose in the European Middle Ages.” I chose to use a mixture of wheat, barley and rye to simulate the “brown bread” eaten by the bourgeois and/or used to make brown trencher breads, as mentioned by the Menagier de Paris.

The shape of the dough, a rounded loaf, is based on many illuminations of bread. I neglected to slash the top, which may have made the loaf denser; however, there are unslashed loaves in some medieval images, which I unfortunately don’t have copies of. The shape of the dough, a rounded loaf, is based on many illuminations of bread. The size of the loaf is based on medieval flour usage – Bread varied in size of loaf, as little as 20 and as many as 35 loaves to the bushel. 25/bushel loaves use 1.38 lb of flour and weighs 1.1 lbs; 35/bushel loaves need .98 lbs flour and weighs .79 lbs after baking. Daily rations averaged about 1 loaf per day, but varied significantly by household (Woolgar, The Great Household in Late Medieval England 124-5).

Once the dough is made and kneaded, the next step is to determine how to bake it. I don’t have a brick oven, so I bought a pizza stone to even out the heat in my modern oven. I also commissioned a baker’s mark from Lord Solvarr Hammarson – as you can see, baking the bread on the bakers mark created an identifying impression in the crust. This was important, since bread was the main food of the Middle Ages (an average daily bread ration was around 2 lbs, in some households) and there were many dishonest bakers – marking the bread allowed fraud to be detected and persecuted.

Sources:

1302597

{1302597:E7XBPRDV},{1302597:2IN5NN46},{1302597:UJ2B8DHG},{1302597:A6GKTCKR},{1302597:3ZFT2MDE},{1302597:Q6J3NPR6},{1302597:IW6CVJT8}

1

modern-language-association

50

creator

asc

82

https://www.erminespot.com/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3Afalse%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22UJ2B8DHG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Carlin%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221998%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BCarlin%2C%20Martha.%20%26%23x201C%3BFast%20Food%20and%20Urban%20Living%20Standards%20in%20Medieval%20England.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BFood%20and%20Eating%20in%20Medieval%20Europe%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%201998%2C%20pp.%2027%26%23x2013%3B51.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Fast%20Food%20and%20Urban%20Living%20Standards%20in%20Medieval%20England%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Martha%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Carlin%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221998%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22BEP5EUGE%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A47%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%223ZFT2MDE%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Fletcher%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222003%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BFletcher%2C%20Jeremy.%20%26%23x201C%3BBakers%26%23x2019%3B%20Marks%3A%20The%20Series.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BThe%20Bread%20Always%20Rises%20in%20the%20West%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%202003%2C%20%26lt%3Ba%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-ItemURL%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.whirlwind-design.com%5C%2Fmadbaker%5C%2Fmarks.html%26%23039%3B%26gt%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.whirlwind-design.com%5C%2Fmadbaker%5C%2Fmarks.html%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Bakers%27%20Marks%3A%20the%20series.%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Jeremy%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Fletcher%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222003%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.whirlwind-design.com%5C%2Fmadbaker%5C%2Fmarks.html%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A40%3A37Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22Q6J3NPR6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Jr.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222006-10-03%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BJr.%2C%20Bernard%20Clayton.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BBernard%20Clayton%26%23x2019%3Bs%20New%20Complete%20Book%20of%20Breads%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20Simon%20%26amp%3B%20Schuster%2C%202006.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Bernard%20Clayton%27s%20New%20Complete%20Book%20of%20Breads%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Bernard%20Clayton%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Jr.%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%5Cu4672%5Cu6f6d%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2062%5Cu6573%5Cu7473%5Cu656c%5Cu6c69%5Cu6e67%5Cu2061%5Cu7574%5Cu686f%5Cu7220%5Cu6f66%5Cu2054%5Cu6865%5Cu204e%5Cu6577%5Cu2043%5Cu6f6d%5Cu706c%5Cu6574%5Cu6520%5Cu426f%5Cu6f6b%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu4272%5Cu6561%5Cu6473%5Cu2063%5Cu6f6d%5Cu6573%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2074%5Cu6869%5Cu7274%5Cu6965%5Cu7468%5Cu2061%5Cu6e6e%5Cu6976%5Cu6572%5Cu7361%5Cu7279%5Cu2065%5Cu6469%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu7468%5Cu6973%5Cu2063%5Cu6c61%5Cu7373%5Cu6963%5Cu2062%5Cu616b%5Cu696e%5Cu6720%5Cu626f%5Cu6f6b%5Cu2c20%5Cu6e6f%5Cu7720%5Cu696e%5Cu2074%5Cu7261%5Cu6465%5Cu2070%5Cu6170%5Cu6572%5Cu6261%5Cu636b%5Cu2e20%5Cu496e%5Cu2074%5Cu6869%5Cu7320%5Cu6578%5Cu6861%5Cu7573%5Cu7469%5Cu7665%5Cu2076%5Cu6f6c%5Cu756d%5Cu652c%5Cu2079%5Cu6f75%5Cu276c%5Cu6c20%5Cu6669%5Cu6e64%5Cu2072%5Cu6563%5Cu6970%5Cu6573%5Cu2066%5Cu6f72%5Cu2065%5Cu7665%5Cu7279%5Cu2069%5Cu6d61%5Cu6769%5Cu6e61%5Cu626c%5Cu6520%5Cu7479%5Cu7065%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu642c%5Cu2066%5Cu726f%5Cu6d20%5Cu7768%5Cu6974%5Cu6520%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu7279%5Cu6520%5Cu746f%5Cu2063%5Cu6865%5Cu6573%5Cu652c%5Cu2068%5Cu6572%5Cu622c%5Cu2046%5Cu7265%5Cu6e63%5Cu682c%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2049%5Cu7461%5Cu6c69%5Cu616e%5Cu2062%5Cu7265%5Cu6164%5Cu732e%5Cu2043%5Cu726f%5Cu6973%5Cu7361%5Cu6e74%5Cu732c%5Cu2062%5Cu7269%5Cu6f63%5Cu6865%5Cu732c%5Cu2066%5Cu6c61%5Cu7420%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu6473%5Cu2c20%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu6372%5Cu6163%5Cu6b65%5Cu7273%5Cu2061%5Cu7265%5Cu2063%5Cu6f76%5Cu6572%5Cu6564%5Cu2069%5Cu6e20%5Cu6465%5Cu7074%5Cu6820%5Cu6173%5Cu2077%5Cu656c%5Cu6c2e%5Cu2048%5Cu6f6d%5Cu6520%5Cu6261%5Cu6b65%5Cu7273%5Cu2077%5Cu696c%5Cu6c20%5Cu6669%5Cu6e64%5Cu2061%5Cu6e20%5Cu6578%5Cu7472%5Cu616f%5Cu7264%5Cu696e%5Cu6172%5Cu7920%5Cu7261%5Cu6e67%5Cu6520%5Cu6f66%5Cu2076%5Cu6172%5Cu6965%5Cu7479%5Cu2c20%5Cu6e65%5Cu6172%5Cu6c79%5Cu2065%5Cu6e6f%5Cu7567%5Cu6820%5Cu746f%5Cu2073%5Cu7570%5Cu706c%5Cu7920%5Cu6120%5Cu6e65%5Cu7720%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu6420%5Cu6120%5Cu6461%5Cu7920%5Cu666f%5Cu7220%5Cu6120%5Cu7965%5Cu6172%5Cu2e20%5Cu5468%5Cu6572%5Cu6520%5Cu6172%5Cu6520%5Cu7768%5Cu6561%5Cu7420%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu6473%5Cu202d%5Cu2d20%5Cu486f%5Cu6e65%5Cu792d%5Cu4c65%5Cu6d6f%5Cu6e2c%5Cu2057%5Cu616c%5Cu6e75%5Cu742c%5Cu2042%5Cu7574%5Cu7465%5Cu726d%5Cu696c%5Cu6b3b%5Cu2073%5Cu6f75%5Cu7264%5Cu6f75%5Cu6768%5Cu2062%5Cu7265%5Cu6164%5Cu733b%5Cu2063%5Cu6f72%5Cu6e20%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu6473%5Cu3b20%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu6473%5Cu2066%5Cu6c61%5Cu766f%5Cu7265%5Cu6420%5Cu7769%5Cu7468%5Cu2068%5Cu6572%5Cu6273%5Cu206f%5Cu7220%5Cu7370%5Cu6963%5Cu6573%5Cu206f%5Cu7220%5Cu656e%5Cu7269%5Cu6368%5Cu6564%5Cu2077%5Cu6974%5Cu6820%5Cu6368%5Cu6565%5Cu7365%5Cu206f%5Cu7220%5Cu6672%5Cu7569%5Cu7473%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu206e%5Cu7574%5Cu733b%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu206c%5Cu6974%5Cu746c%5Cu6520%5Cu6272%5Cu6561%5Cu6473%5Cu202d%5Cu2d20%5Cu4b61%5Cu6973%5Cu6572%5Cu2052%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6c73%5Cu2c20%5Cu4772%5Cu616e%5Cu646d%5Cu6f74%5Cu6865%5Cu7227%5Cu7320%5Cu536f%5Cu7574%5Cu6865%5Cu726e%5Cu2042%5Cu6973%5Cu6375%5Cu6974%5Cu732c%5Cu2045%5Cu6e67%5Cu6c69%5Cu7368%5Cu204d%5Cu7566%5Cu6669%5Cu6e73%5Cu2c20%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu506f%5Cu706f%5Cu7665%5Cu7273%5Cu2c20%5Cu746f%5Cu206e%5Cu616d%5Cu6520%5Cu6120%5Cu6665%5Cu772e%5Cu2046%5Cu6f72%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2062%5Cu616b%5Cu6572%5Cu2077%5Cu686f%5Cu206f%5Cu6273%5Cu6572%5Cu7665%5Cu7320%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu686f%5Cu6c69%5Cu6461%5Cu7973%5Cu2077%5Cu6974%5Cu6820%5Cu6120%5Cu6672%5Cu6573%5Cu6820%5Cu6c6f%5Cu6166%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu7265%5Cu2061%5Cu7265%5Cu2043%5Cu6861%5Cu6c6c%5Cu6168%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2049%5Cu7461%5Cu6c69%5Cu616e%5Cu2050%5Cu616e%5Cu6574%5Cu746f%5Cu6e65%5Cu2e43%5Cu6c61%5Cu7974%5Cu6f6e%5Cu2061%5Cu6c73%5Cu6f20%5Cu636f%5Cu7665%5Cu7273%5Cu2074%5Cu6f70%5Cu6963%5Cu7320%5Cu6c69%5Cu6b65%5Cu2073%5Cu7461%5Cu7274%5Cu6572%5Cu7320%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu7374%5Cu6f72%5Cu696e%5Cu6720%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu6672%5Cu6565%5Cu7a69%5Cu6e67%5Cu2062%5Cu7265%5Cu6164%5Cu732c%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2064%5Cu6576%5Cu6f74%5Cu6573%5Cu2061%5Cu6e20%5Cu656e%5Cu7469%5Cu7265%5Cu2063%5Cu6861%5Cu7074%5Cu6572%5Cu2074%5Cu6f20%5Cu2257%5Cu6861%5Cu7420%5Cu5765%5Cu6e74%5Cu2057%5Cu726f%5Cu6e67%5Cu202d%5Cu2d20%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu486f%5Cu7720%5Cu746f%5Cu204d%5Cu616b%5Cu6520%5Cu4974%5Cu2052%5Cu6967%5Cu6874%5Cu2e22%5Cu2050%5Cu6572%5Cu6665%5Cu6374%5Cu2066%5Cu6f72%5Cu2061%5Cu6c6c%5Cu206c%5Cu6576%5Cu656c%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu2062%5Cu616b%5Cu6572%5Cu732c%5Cu2074%5Cu6869%5Cu7320%5Cu626f%5Cu6f6b%5Cu2077%5Cu616c%5Cu6b73%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu206e%5Cu6f76%5Cu6963%5Cu6520%5Cu7468%5Cu726f%5Cu7567%5Cu6820%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu7374%5Cu6570%5Cu7320%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu656e%5Cu636f%5Cu7572%5Cu6167%5Cu6573%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2061%5Cu6476%5Cu616e%5Cu6365%5Cu6420%5Cu6261%5Cu6b65%5Cu7220%5Cu746f%5Cu2074%5Cu7279%5Cu206e%5Cu6577%5Cu2076%5Cu6172%5Cu6961%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu7320%5Cu6f6e%5Cu2072%5Cu6563%5Cu6970%5Cu6573%5Cu2e44%5Cu6576%5Cu6f74%5Cu6564%5Cu2066%5Cu616e%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu2042%5Cu6572%5Cu6e61%5Cu7264%5Cu2043%5Cu6c61%5Cu7974%5Cu6f6e%5Cu2077%5Cu696c%5Cu6c20%5Cu6265%5Cu2074%5Cu6872%5Cu696c%5Cu6c65%5Cu6420%5Cu7769%5Cu7468%5Cu2074%5Cu6869%5Cu7320%5Cu6561%5Cu7379%5Cu2d74%5Cu6f2d%5Cu7573%5Cu6520%5Cu7061%5Cu7065%5Cu7262%5Cu6163%5Cu6b20%5Cu6564%5Cu6974%5Cu696f%5Cu6e20%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu6465%5Cu6c69%5Cu6768%5Cu7465%5Cu6420%5Cu746f%5Cu2073%5Cu6565%5Cu206f%5Cu6c64%5Cu2066%5Cu6176%5Cu6f72%5Cu6974%5Cu6573%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2074%5Cu7279%5Cu206e%5Cu6577%5Cu206f%5Cu6e65%5Cu732e%5Cu2054%5Cu6869%5Cu7320%5Cu6973%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2064%5Cu6566%5Cu696e%5Cu6974%5Cu6976%5Cu6520%5Cu6564%5Cu6974%5Cu696f%5Cu6e20%5Cu6f66%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2063%5Cu6c61%5Cu7373%5Cu6963%5Cu2062%5Cu616b%5Cu696e%5Cu6720%5Cu626f%5Cu6f6b%5Cu2074%5Cu6861%5Cu7420%5Cu6576%5Cu6572%5Cu7920%5Cu676f%5Cu6f64%5Cu2063%5Cu6f6f%5Cu6b20%5Cu7368%5Cu6f75%5Cu6c64%5Cu206f%5Cu776e%3F%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22October%203%2C%202006%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-0-7432-8709-8%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A47%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22E7XBPRDV%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Scully%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222005%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BScully%2C%20Terence.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BThe%20Art%20of%20Cookery%20in%20the%20Middle%20Ages%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20Boydell%20Pr%2C%202005%2C%20%26lt%3Ba%20class%3D%26%23039%3Bzp-ItemURL%26%23039%3B%20href%3D%26%23039%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fbooks.google.com%5C%2Fbooks%3Fhl%3Den%26amp%3Blr%3D%26amp%3Bid%3Di5h7_HXPHvwC%26amp%3Boi%3Dfnd%26amp%3Bpg%3DPA1%26amp%3Bdq%3DThe%2BArt%2Bof%2BCookery%2Bin%2Bthe%2BMiddle%2BAges%26amp%3Bots%3DhW0i0sx9GE%26amp%3Bsig%3D1i6bF_Lz7De0GaOmpQt14IIFzhg%26%23039%3B%26gt%3Bhttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fbooks.google.com%5C%2Fbooks%3Fhl%3Den%26amp%3Blr%3D%26amp%3Bid%3Di5h7_HXPHvwC%26amp%3Boi%3Dfnd%26amp%3Bpg%3DPA1%26amp%3Bdq%3DThe%2BArt%2Bof%2BCookery%2Bin%2Bthe%2BMiddle%2BAges%26amp%3Bots%3DhW0i0sx9GE%26amp%3Bsig%3D1i6bF_Lz7De0GaOmpQt14IIFzhg%26lt%3B%5C%2Fa%26gt%3B.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20art%20of%20cookery%20in%20the%20Middle%20Ages%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Terence%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Scully%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222005%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fbooks.google.com%5C%2Fbooks%3Fhl%3Den%26lr%3D%26id%3Di5h7_HXPHvwC%26oi%3Dfnd%26pg%3DPA1%26dq%3DThe%2BArt%2Bof%2BCookery%2Bin%2Bthe%2BMiddle%2BAges%26ots%3DhW0i0sx9GE%26sig%3D1i6bF_Lz7De0GaOmpQt14IIFzhg%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%228WPQ9TAG%22%2C%22BEP5EUGE%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A41%3A04Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%222IN5NN46%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Scully%20and%20Scully%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221995%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BScully%2C%20D.%20Eleanor%2C%20and%20Terence%20Scully.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BEarly%20French%20Cookery%26%23x202F%3B%3A%20Sources%2C%20History%2C%20Original%20Recipes%20and%20Modern%20Adaptations%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20University%20of%20Michigan%20Press%2C%201995.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Early%20French%20cookery%20%3A%20sources%2C%20history%2C%20original%20recipes%20and%20modern%20adaptations%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22D.%20Eleanor%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Scully%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Terence%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Scully%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221995%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%2C%20with%20some%20recipes%20in%20English%20and%20French.%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%220-472-10648-1%20978-0-472-10648-6%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%228WPQ9TAG%22%2C%22BEP5EUGE%22%2C%22RIFVUTS2%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A40%3A42Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22A6GKTCKR%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Swabey%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221998%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BSwabey%2C%20Ffiona.%20%26%23x201C%3BThe%20Household%20of%20Alice%20de%20Bryenne%2C%201412-1413.%26%23x201D%3B%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BFood%20and%20Eating%20in%20Medieval%20Europe%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B%2C%201998%2C%20pp.%20133%26%23x2013%3B44.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Household%20of%20Alice%20de%20Bryenne%2C%201412-1413%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Ffiona%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Swabey%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221998%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22BEP5EUGE%22%2C%22RIFVUTS2%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A47%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22IW6CVJT8%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1302597%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Woolgar%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%221999%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-bib-body%26quot%3B%20style%3D%26quot%3Bline-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%26quot%3B%26gt%3B%5Cn%20%20%26lt%3Bdiv%20class%3D%26quot%3Bcsl-entry%26quot%3B%26gt%3BWoolgar%2C%20C.%20M.%20%26lt%3Bi%26gt%3BThe%20Great%20Household%20in%20Late%20Medieval%20England%26lt%3B%5C%2Fi%26gt%3B.%20Yale%20University%20Press%2C%201999.%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%5Cn%26lt%3B%5C%2Fdiv%26gt%3B%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22book%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20great%20household%20in%20late%20medieval%20England%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22C.%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Woolgar%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%5Cu496e%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu206c%5Cu6174%5Cu6572%5Cu206d%5Cu6564%5Cu6965%5Cu7661%5Cu6c20%5Cu6365%5Cu6e74%5Cu7572%5Cu6965%5Cu732c%5Cu2061%5Cu2077%5Cu686f%5Cu6c65%5Cu2072%5Cu616e%5Cu6765%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu696d%5Cu706f%5Cu7274%5Cu616e%5Cu7420%5Cu736f%5Cu6369%5Cu616c%5Cu2c20%5Cu706f%5Cu6c69%5Cu7469%5Cu6361%5Cu6c2c%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2061%5Cu7274%5Cu6973%5Cu7469%5Cu6320%5Cu6163%5Cu7469%5Cu7669%5Cu7469%5Cu6573%5Cu2074%5Cu6f6f%5Cu6b20%5Cu706c%5Cu6163%5Cu6520%5Cu6167%5Cu6169%5Cu6e73%5Cu7420%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu6261%5Cu636b%5Cu6472%5Cu6f70%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu6772%5Cu6561%5Cu7420%5Cu456e%5Cu676c%5Cu6973%5Cu6820%5Cu686f%5Cu7573%5Cu6568%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6473%5Cu2e20%5Cu496e%5Cu2074%5Cu6869%5Cu7320%5Cu6c69%5Cu7665%5Cu6c79%5Cu2062%5Cu6f6f%5Cu6b2c%5Cu2043%5Cu2e20%5Cu4d2e%5Cu2057%5Cu6f6f%5Cu6c67%5Cu6172%5Cu2065%5Cu7870%5Cu6c6f%5Cu7265%5Cu7320%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu6661%5Cu7363%5Cu696e%5Cu6174%5Cu696e%5Cu6720%5Cu6465%5Cu7461%5Cu696c%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu206c%5Cu6966%5Cu6520%5Cu696e%5Cu2061%5Cu2067%5Cu7265%5Cu6174%5Cu2068%5Cu6f75%5Cu7365%5Cu2e20%5Cu4261%5Cu7365%5Cu6420%5Cu6f6e%5Cu2065%5Cu7874%5Cu656e%5Cu7369%5Cu7665%5Cu2069%5Cu6e76%5Cu6573%5Cu7469%5Cu6761%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu686f%5Cu7573%5Cu6568%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6420%5Cu6163%5Cu636f%5Cu756e%5Cu7473%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2072%5Cu656c%5Cu6174%5Cu6564%5Cu2070%5Cu7269%5Cu6d61%5Cu7279%5Cu2064%5Cu6f63%5Cu756d%5Cu656e%5Cu7473%5Cu2c20%5Cu576f%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6761%5Cu7220%5Cu7669%5Cu7669%5Cu646c%5Cu7920%5Cu696c%5Cu6c75%5Cu6d69%5Cu6e61%5Cu7465%5Cu7320%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu6f70%5Cu6572%5Cu6174%5Cu696f%5Cu6e73%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu6772%5Cu6561%5Cu7420%5Cu686f%5Cu7573%5Cu6568%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6473%5Cu2e20%5Cu4865%5Cu2061%5Cu6c73%5Cu6f20%5Cu6465%5Cu6c69%5Cu6e65%5Cu6174%5Cu6573%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu206d%5Cu616a%5Cu6f72%5Cu2063%5Cu6861%5Cu6e67%5Cu6573%5Cu2074%5Cu6861%5Cu7420%5Cu7472%5Cu616e%5Cu7366%5Cu6f72%5Cu6d65%5Cu6420%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu6563%5Cu6f6e%5Cu6f6d%5Cu7920%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu6765%5Cu6f67%5Cu7261%5Cu7068%5Cu7920%5Cu6f66%5Cu2062%5Cu6f74%5Cu6820%5Cu6c61%5Cu7920%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu636c%5Cu6572%5Cu6963%5Cu616c%5Cu2068%5Cu6f75%5Cu7365%5Cu686f%5Cu6c64%5Cu7320%5Cu6265%5Cu7477%5Cu6565%5Cu6e20%5Cu3132%5Cu3030%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2031%5Cu3530%5Cu302e%5Cu2020%5Cu496e%5Cu2074%5Cu6869%5Cu7320%5Cu706f%5Cu7274%5Cu7261%5Cu6974%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu6172%5Cu6973%5Cu746f%5Cu6372%5Cu6174%5Cu6963%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2067%5Cu656e%5Cu7472%5Cu7920%5Cu6c69%5Cu6665%5Cu2069%5Cu6e20%5Cu6d65%5Cu6469%5Cu6576%5Cu616c%5Cu2045%5Cu6e67%5Cu6c61%5Cu6e64%5Cu2c20%5Cu576f%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6761%5Cu7220%5Cu6465%5Cu7363%5Cu7269%5Cu6265%5Cu7320%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu726f%5Cu6c65%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu2066%5Cu616d%5Cu696c%5Cu7920%5Cu6d65%5Cu6d62%5Cu6572%5Cu732c%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2073%5Cu6974%5Cu7561%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu2073%5Cu6572%5Cu7661%5Cu6e74%5Cu732c%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2075%5Cu7365%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu2073%5Cu7061%5Cu6365%5Cu2077%5Cu6974%5Cu6869%5Cu6e20%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu686f%5Cu7573%5Cu6568%5Cu6f6c%5Cu642c%5Cu2066%5Cu6f6f%5Cu6420%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu6472%5Cu696e%5Cu6b20%5Cu666f%5Cu7220%5Cu6461%5Cu696c%5Cu7920%5Cu636f%5Cu6e73%5Cu756d%5Cu7074%5Cu696f%5Cu6e20%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu666f%5Cu7220%5Cu7370%5Cu6563%5Cu6961%5Cu6c20%5Cu6f63%5Cu6361%5Cu7369%5Cu6f6e%5Cu732c%5Cu2066%5Cu7572%5Cu6e69%5Cu7368%5Cu696e%5Cu672c%5Cu2063%5Cu6c6f%5Cu7468%5Cu696e%5Cu672c%5Cu2061%5Cu7272%5Cu616e%5Cu6765%5Cu6d65%5Cu6e74%5Cu7320%5Cu666f%5Cu7220%5Cu7472%5Cu6176%5Cu656c%5Cu2c20%5Cu686f%5Cu7573%5Cu6568%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6420%5Cu616e%5Cu696d%5Cu616c%5Cu732c%5Cu2063%5Cu6c65%5Cu616e%5Cu6c69%5Cu6e65%5Cu7373%5Cu2061%5Cu6e64%5Cu2068%5Cu7967%5Cu6965%5Cu6e65%5Cu2c20%5Cu656e%5Cu7465%5Cu7274%5Cu6169%5Cu6e6d%5Cu656e%5Cu742c%5Cu2074%5Cu6865%5Cu2070%5Cu7261%5Cu6374%5Cu6963%5Cu6573%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu7265%5Cu6c69%5Cu6769%5Cu6f6e%5Cu2c20%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu696e%5Cu7465%5Cu6c6c%5Cu6563%5Cu7475%5Cu616c%5Cu206c%5Cu6966%5Cu652e%5Cu2054%5Cu6865%5Cu2061%5Cu7574%5Cu686f%5Cu7220%5Cu616c%5Cu736f%5Cu2061%5Cu6e61%5Cu6c79%5Cu7a65%5Cu7320%5Cu7468%5Cu6520%5Cu7175%5Cu616c%5Cu6974%5Cu6174%5Cu6976%5Cu6520%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu736f%5Cu6369%5Cu616c%5Cu2065%5Cu766f%5Cu6c75%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu206f%5Cu6620%5Cu6772%5Cu6561%5Cu7420%5Cu686f%5Cu7573%5Cu6568%5Cu6f6c%5Cu6473%5Cu2061%5Cu7320%5Cu6465%5Cu6669%5Cu6e69%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu206d%5Cu6167%5Cu6e69%5Cu6669%5Cu6365%5Cu6e63%5Cu6520%5Cu616e%5Cu6420%5Cu636f%5Cu6e76%5Cu656e%5Cu7469%5Cu6f6e%5Cu7320%5Cu6f66%5Cu2065%5Cu7469%5Cu7175%5Cu6574%5Cu7465%5Cu2062%5Cu6563%5Cu616d%5Cu6520%5Cu696e%5Cu6372%5Cu6561%5Cu7369%5Cu6e67%5Cu6c79%5Cu2065%5Cu6c61%5Cu626f%5Cu7261%5Cu7465%3F%22%2C%22date%22%3A%221999%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22ISBN%22%3A%22978-0-300-07687-5%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22BEP5EUGE%22%2C%22RIFVUTS2%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222025-04-18T01%3A47%3A44Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

Carlin, Martha. “Fast Food and Urban Living Standards in Medieval England.” Food and Eating in Medieval Europe , 1998, pp. 27–51.

Fletcher, Jeremy. “Bakers’ Marks: The Series.”

The Bread Always Rises in the West , 2003,

http://www.whirlwind-design.com/madbaker/marks.html .

Jr., Bernard Clayton. Bernard Clayton’s New Complete Book of Breads . Simon & Schuster, 2006.

Scully, D. Eleanor, and Terence Scully. Early French Cookery : Sources, History, Original Recipes and Modern Adaptations . University of Michigan Press, 1995.

Swabey, Ffiona. “The Household of Alice de Bryenne, 1412-1413.” Food and Eating in Medieval Europe , 1998, pp. 133–44.

Woolgar, C. M. The Great Household in Late Medieval England . Yale University Press, 1999.

4 Comments

You “redacted” the recipe???

It’s an SCA thing – I’m not sure why that’s the word used, but nonetheless. Someone else describes it here: https://www.bakerspeel.com/redacting-a-recipe/